Five years ago, I wrote an article for Sustainable Architecture and Building (SAB) Magazine called Social Sustainability in Practice. Back then, our practice had begun defining a framework for social impact as a strategy to re-orient sustainability. Our goal? To shine light on the often-missing social dimension.

I saw it as a chance to call our industry to action. I was frustrated with the emphasis on environmental performance in sustainable design, which too often ignored the importance of social relationships, cultural beliefs, and political structures.

Our public buildings, I firmly believed, must do more than simply provide green programming or service space. They should be inspiring and inclusive spaces that combat loneliness, build community resilience, and reduce the stigma and barriers of disability through accessible design – while simultaneously minimizing their impact on the planet.

Darryl Condon on embracing the journey of our time—dignifying people and the planet as one.

With contributions from Rebecca Holt, Fiona Jones and Marni Robinson.

An abridged version of this work was originally published in March 2021 by DesignIntelligence: In The Balance: The Future of Environmental Responsibility – Essays.

To strengthen our approach, I proposed a social impact framework – a tool we have been using to quantify previously ‘difficult-to-measure’ project goals, based on our research of hundreds of potential indicators of social sustainability. Since creating the framework, we have been experimenting with it on our projects, and evolving it based on what we’ve learnt along the way.

Despite measurable progress in using the framework on select projects, broader progress has been slow. My frustration persists. Architects and city builders who were once comfortable addressing social impacts have since looked away. And yet, we can no longer ignore our responsibility to the social aspects of design. It’s time to re-engage.

One thing I regret from my 2015 article is any implication that what we then called ‘social sustainability’ was more important, or in any way disconnected, from the environmental discussion. As I reflect on my words, I'm reminded of the Brundtland Report, Our Common Future. In defining sustainability with simplicity and purpose, that report set the course for the formal practice of sustainable design. In the Chair’s Foreword, Gro Harlem Brundtland eloquently describes the environment and social life as one and the same:

“But the ‘environment’ is where we all live; and ‘development’ is what we all do in attempting to improve our lot within that abode. The two are inseparable.” [1]

The report goes on to confirm that sustainability is not a state – it is rather a process of change. It reminds us that this process is complex. It’s not easy or comfortable. And reflecting on the challenges in our journey to define and evolve our social impact framework, this statement lends comfort: it’s a process. It’s complex. It’s difficult. We have evolved our thinking, but still have work to do.

In November 2020, Vancouver’s City Council voted to adopt its ambitious Climate Emergency Action Plan, which offered a glimmer of hope that we are heading in the right direction. At the time, we wrote to Council in support of the plan, which boldly connects all strategies to equity.

We are hopeful it will have ripple effects on climate policy around the world – specifically, positioning the conversation within an understanding that the health and flourishing of the planet is inseparable from that of people.

I hope that by sharing our journey, others will feel inspired to share theirs too, and together we can contribute to the design community’s knowledge base.

Why are social factors important?

Design creates value, which is determined by the systems, structures, priorities, and expectations in which we work. But I also believe design is about values.

To assess them in practice, we need an integrated approach to sustainability. We need to ask, “What are we sustaining; why are we sustaining it – and for whom?”

These questions give us a chance to reframe the aspirations of our projects. They push us to embrace the social performance alongside environmental performance.

This reframing also helps us identify when our processes and strategies to maximize social and environmental performance are aligned and amplify each other. For example, factors we thought would improve climate resilience are proving important in supporting safe, healthy social connection during the COVID-19 pandemic—things like weather-protected outdoor gathering spaces or active transportation infrastructure. Sometimes, however, these strategies are at odds, requiring critical and creative approaches to decision-making and prioritization.

To maximize positive impact, projects need to examine the unique values, challenges, and opportunities to create context-specific strategies and responses. These are crucial to individual project success; they help us better solve problems across the project.

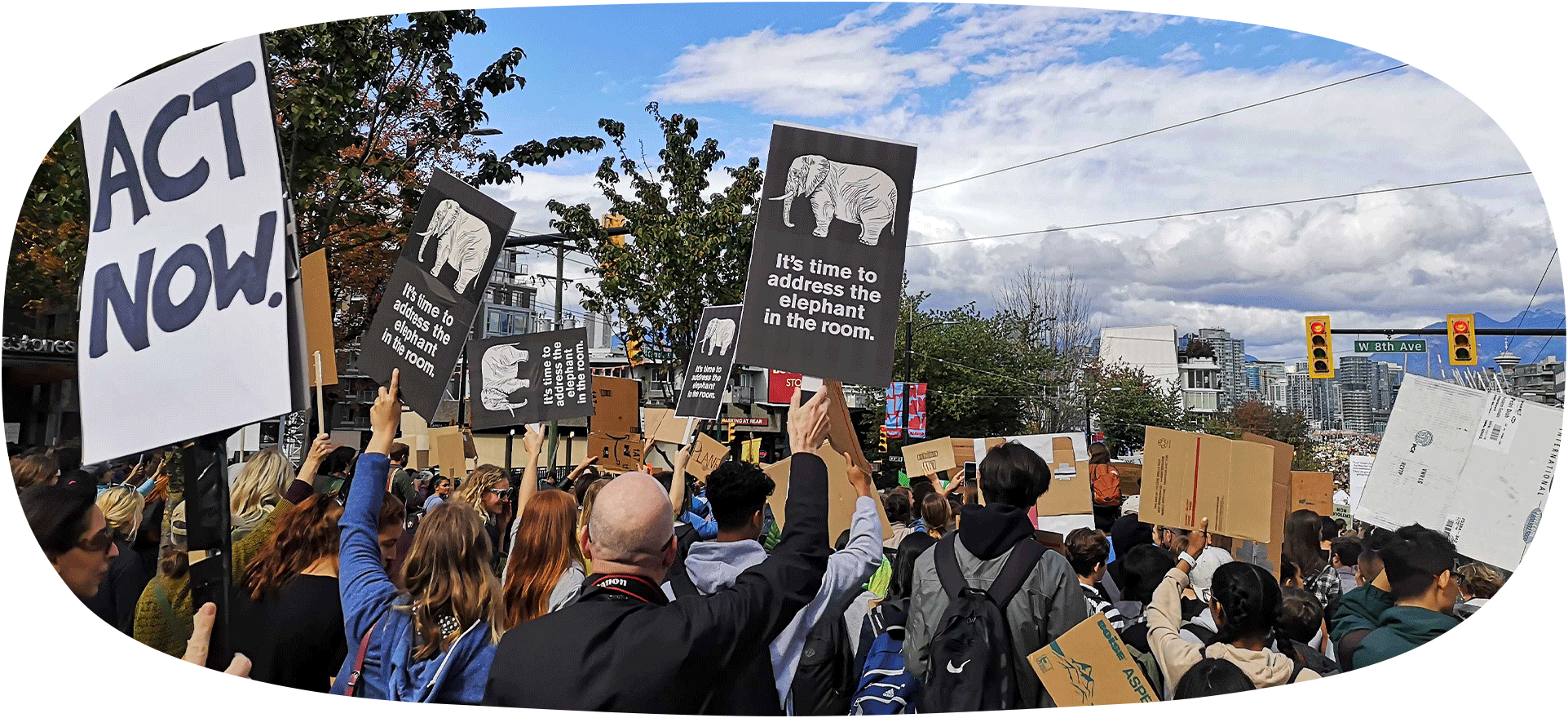

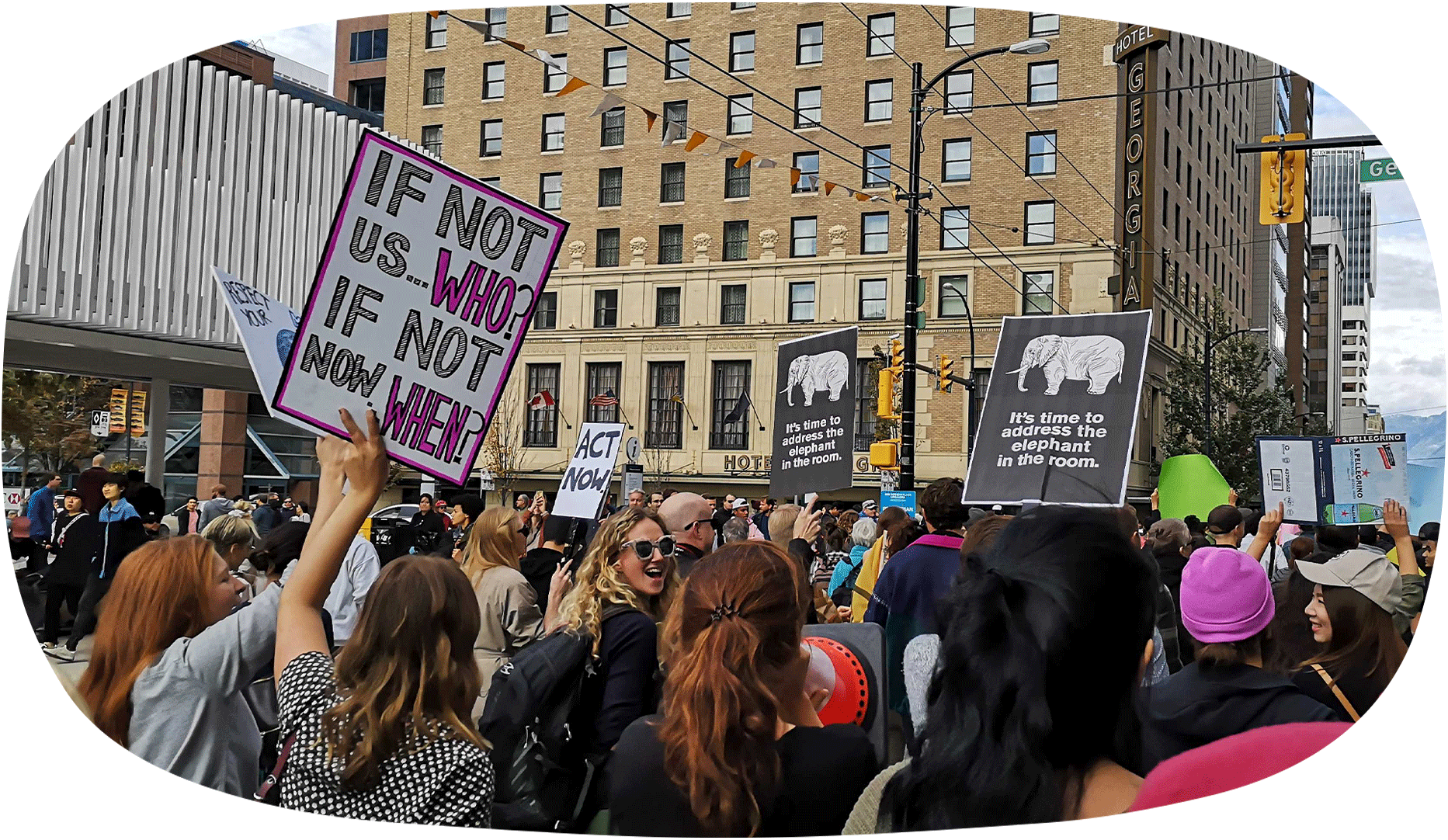

Darryl and the hcma team participating in the Vancouver Climate March in September 2019, spreading the message that it’s time to address the elephant in the room: the climate emergency

Image Credit: hcma

Even more effective are policy and governance shifts. They are powerful when prioritizing integrated action on sustainability and are most scalable across multiple projects. When used effectively, we’ve seen cities and industries improve how they meet climate commitments, catalyzed by large-scale systemic revolution, rather than incremental change.

To contribute to this impact, designers and planners must also become policy change advocates.

Learning and unlearning

In the five years since the SAB article, the world has continued to evolve in ways both familiar and unimaginably strange. Our design context is being shaped—as it always has—by current political, cultural, and natural events.

In the wake of what we’ve learned recently from global Black Lives Matter protests and the recommendations made by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, we must challenge ourselves to face and acknowledge the lasting impacts of colonization, discrimination, and unconscious bias.

We know we have a long way to go. We must be committed to learning and unlearning, to understand how privilege has shaped our work, and how we can use design to increase equity in the communities we serve.

We learn by listening and engaging with individuals and communities with different voices, perspectives, and backgrounds. By pushing ourselves to dig deeper – beyond stereotypes, best practices, or sweeping generalizations.

We unlearn by challenging our own entrenched belief systems; by re-examining readily-accepted design principles that may, in fact, exclude and discriminate. At hcma, for instance, we are beginning to question what projects we should (or should not) take on.

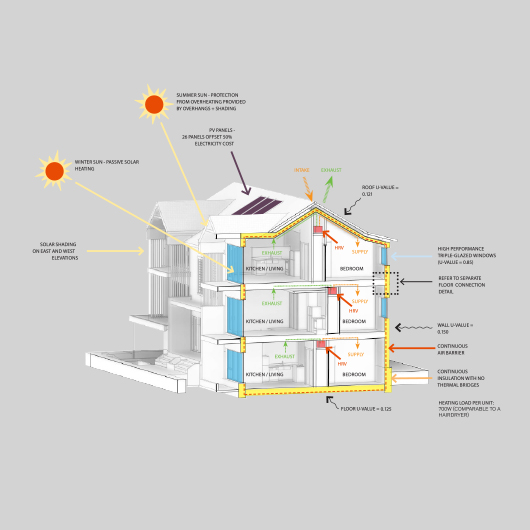

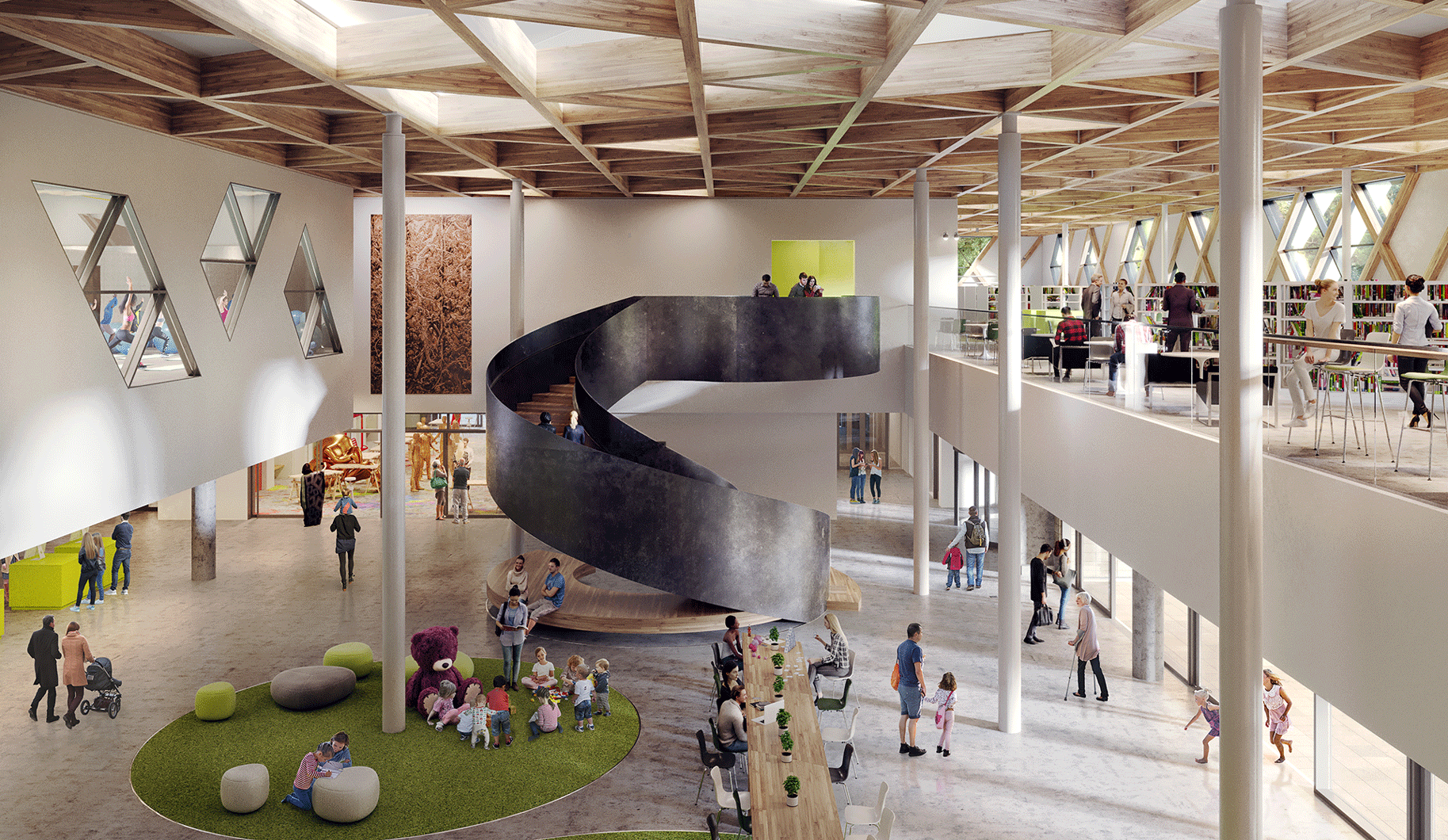

The new Clayton Community Centre in Surrey, BC provides a social hub for the community with its integrated library, performance and recreation facilities with the highest energy efficiency. It will be the first community centre in North America to achieve Passive House standard.

Image Credit: hcma

Decentring our perspective

To strengthen, influence, and evolve our understanding and beliefs about sustainability, we must first understand the notion of ‘decentring’, which is defined as a shift away from an established centre or focus; the act of disconnecting from practical and theoretical assumptions based on origin, priority, or essence.

1. Decentring whiteness

Architects in North America and Europe have only just begun to accept that our profession has a race problem. The industry has been – and remains – overwhelmingly white. This lack of diversity is based on a legacy of conscious and unconscious biases, which continue to shape inclusivity and access to public and private infrastructure.

American architect, Bryan Lee Jr. of Colloqate, has spoken extensively on the concept of design justice. He notes: “For nearly every injustice in the world, there is an architecture that has been planned and designed to perpetuate it.”[2]

In Canada, we must also face up to our troubled history with the erasure of Indigenous people, their lands and their culture. Locally, Indigenous changemakers like Ginger Gosnell-Myers (Nisga'a and Kwakwak'awakw) and Ta7talíya Michelle Nahanee (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh) have advocated for design that acknowledges the wrongs of the past while moving toward a new future, together.

We’re also inspired by the reconciliation work being done in New Zealand, where representatives of Te Kāhui Whaihanga New Zealand Institute of Architects and Ngā Aho, the society of Māori design professionals, signed Te Kawenata o Rata, a covenant that formalises an ongoing relationship of co-operation between the two groups. It also identifies design principles that enable Māori values to be incorporated into the design process.[3]

2. Decentring humans

Humans tend to place themselves at the top and centre of things – it is evident in the way we treat nature and the environment. As proponents of design inclusivity, we’ve recently been challenged to think more deeply about what ‘decentring the human’ means.

Matthew Hickey, Mohawk Architect and Partner at Two Row Architect (which operates from the Six Nations reserve in southern Ontario), describes a concept he calls ‘universal inclusivity’. He challenges us to extend inclusivity beyond human identity to encompass ‘not just every-one but every-thing’.

This idea “goes beyond physical abilities, race, gender, and into species, climate and the land itself.”[4]

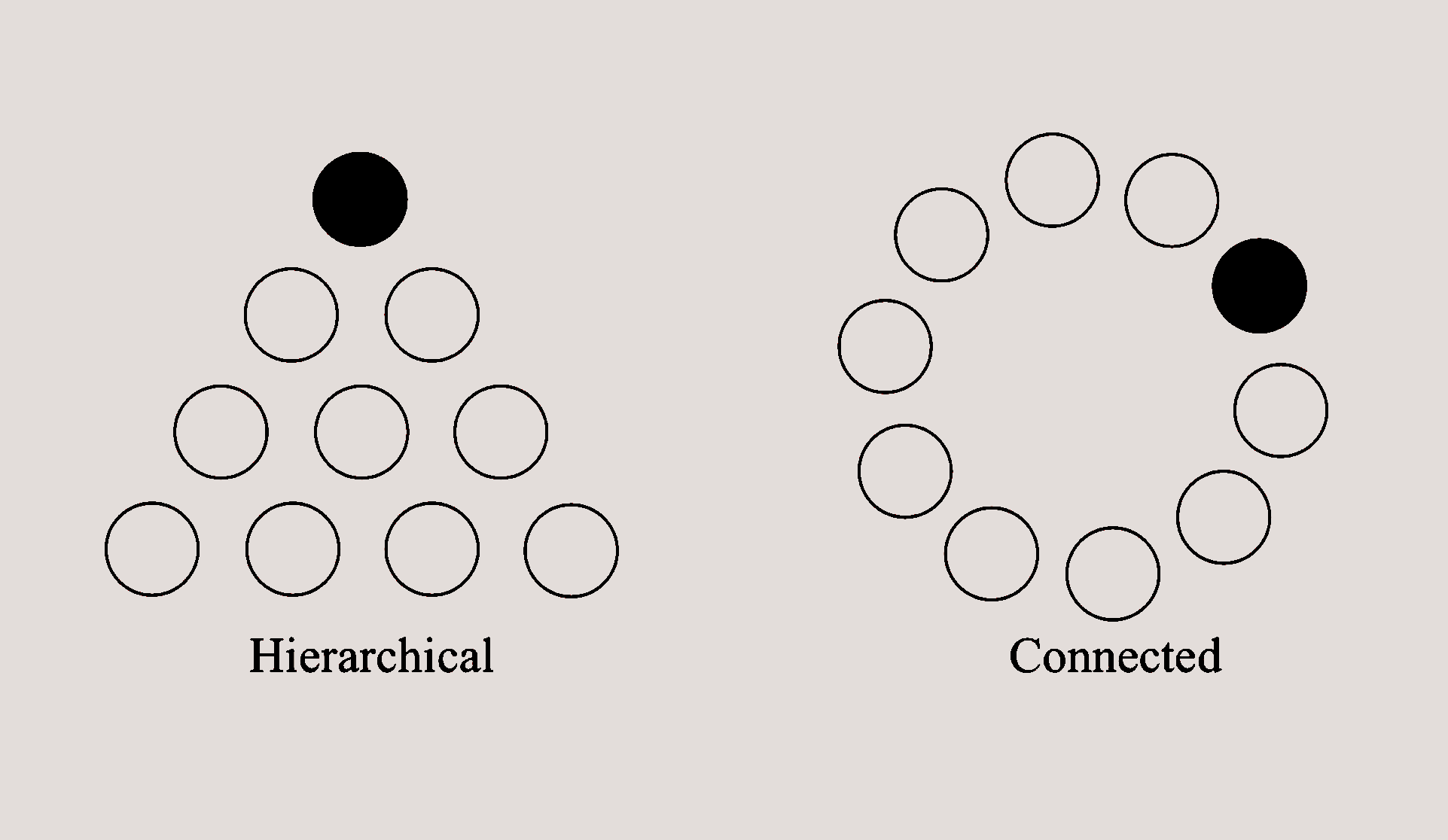

It helps us answer the question of how we can create more equitable places and cities when the built environment too often reinforces artificial hierarchies. It shows us what design could look like if we were to also value non-human life.

Repositioning ourselves within broader systems is crucial, says Hickey, because:

“All of these big questions reflect the same philosophy – one that removes us humans from having domination over the land and places us in an equal partnership with the world around us. Decolonizing the way we think about design and architecture and the processes by which we create the built environment begins with taking humans off the top of the pyramid and placing them as an equal part of a circle.”[5]

For too long, we have assumed the planet is here for our benefit – and so we’ve exploited its resources for human benefit, rather than realizing we are part of a delicate and interconnected ecosystem.

When we decentre humans, we put value on interdependence with other agents in our local and planetary systems. We restructure and re-orient the power and relationships in those systems.

At first glance, this may seem paradoxical. We are, after all, practitioners who recognize the value of the human-centred design movement and emphasize the social impact potential of our work.

But we must rebuild deeper connections to the systems that sustain life for humans and all other species. In doing this, we inherently increase equity and justice – along with a balance we have nearly lost sight of.

3. Decentring economic value and profits

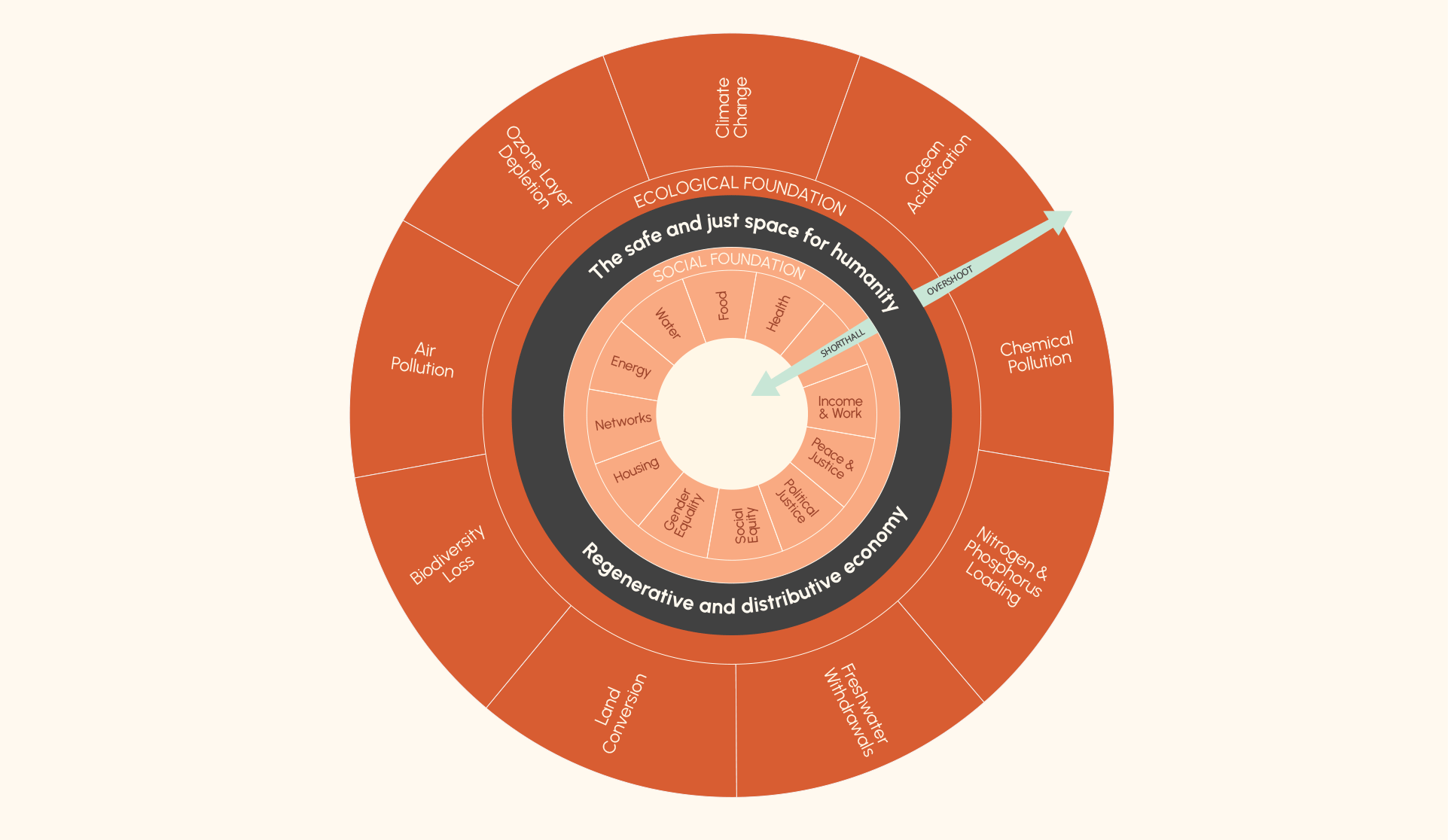

We’re inspired by economist Kate Raworth’s theory of Doughnut Economics.[7] Its memorable name and simple diagram aptly illustrate a robust philosophy of balance.

Raworth challenges economic systems that neither value human life, nor the life and finite resources of the planet. She advocates that the ‘safe and just space for humanity’ exists not at the centre but between two key realms: our necessary social foundation and our ecological ceiling. This balance, she argues, is achieved by creating regenerative, distributive economies.

Her model is compelling. It builds upon Johan Rockström and the Stockholm Resilience Institute’s 2009 publication of the Nine Planetary Boundaries Framework, and again in 2015.[8]

Their work determined a safe operating space for humanity from the preceding decades of earth system science. Raworth’s model then layers the boundaries of social conditions into these planetary boundaries, based on the minimum social conditions established by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015. It is within these social and planetary boundaries that we may find a safe and just planet.

The model rejects the pursuit of unbridled profit that degrades all life on the planet while exacerbating the concentration of obscene wealth in the pockets of a few. It reinforces an integrated approach to sustainability, where social and environmental performance are no longer at odds.

We see the challenge and goal of this model as learning to stay within this healthy middle ground. We achieve it through dynamic strategies and negotiation of methods and priorities—much how a thermostat functions, by keeping a room temperature fluctuating within a specified range.

The middle space reminds us that our economic systems and structures are constructs we have created. Therefore, we can re-create them to have different goals and embedded inertias.

Where we’re heading

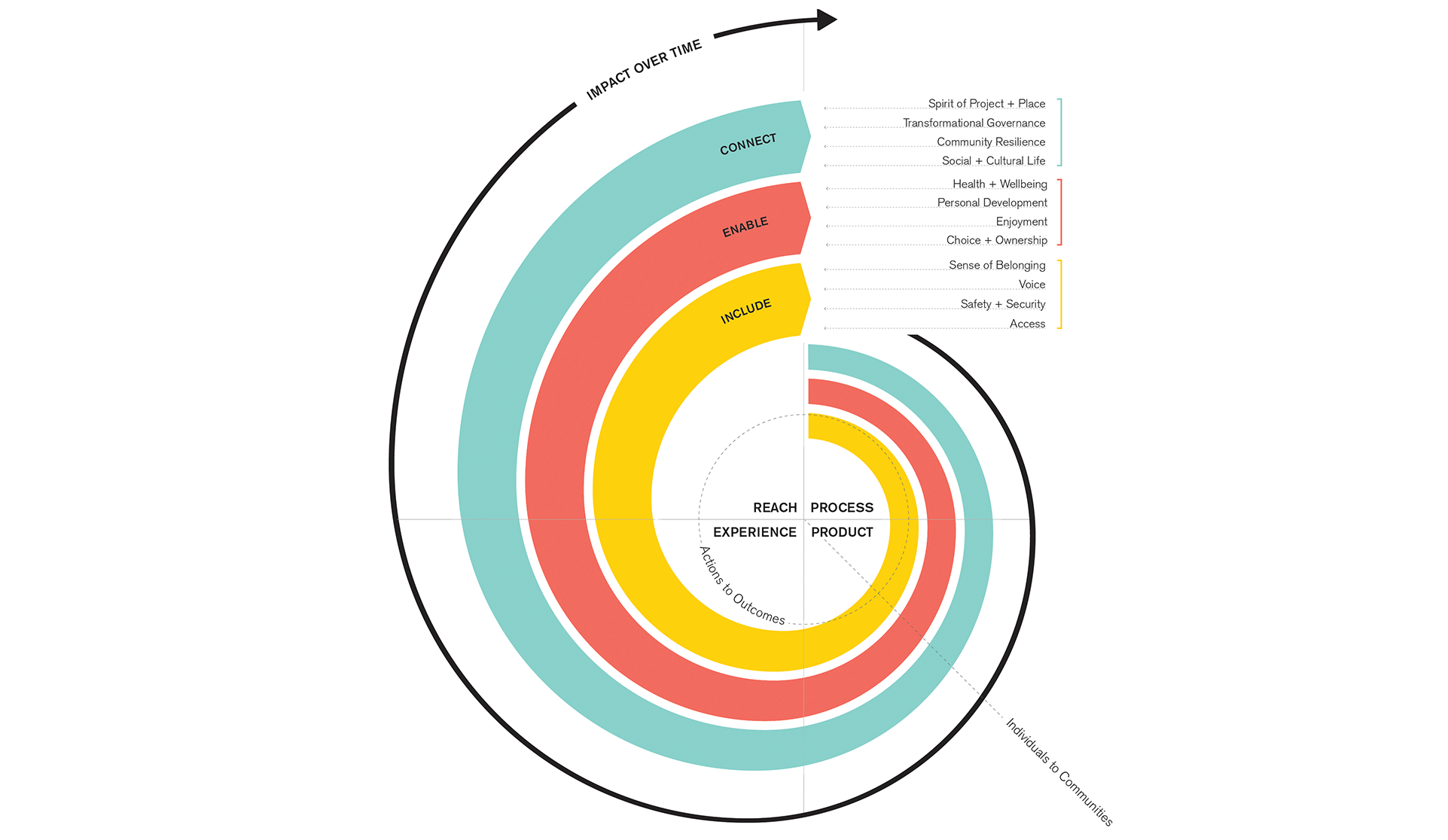

Our evolving Social Impact Framework continues to guide our work and conversations. We are developing it as a shared open asset that reflects the learnings and questions we have collected over years of work and research.

Within this framework, we are strengthening our approach to integrated sustainability by bringing our understanding, shared language, and social impact performance accountability closer to that of environmental performance.

The framework emphasizes equity and dignity, building on the work of countless others – and highlighting voices, organizations, and projects that have influenced and inspired us.

To further guide our journey, we have defined three imperatives: include, enable, connect. Each of these contains a number of categories, which outline how social impact relates to design and its cumulative effects over time.

From ‘sense of belonging’ to ‘enjoyment’ to 'social and cultural life’ to ‘transformational governance’, each category contains indicators for which we are developing process strategies, design strategies, and assessment ideas.

We have found that the framework acts as a ‘North Star’ for our clients, and aids with project visioning and goal setting. We’re working with in-house research specialists and other collaborators to develop assessment methods to better understand links between strategies and outcomes—with exciting promise.

Beyond supporting discourse, we’re investing in positive impact in other ways. Our firm is taking on anti-racism work through training, structured learning and unlearning challenges, and internal policies and procedure reviews.

For the first time, we are asking equity-related demographics questions in employee engagement surveys, to understand who we are as hcma-ers and better address issues of justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion.

Likewise, our Artist in Residence program and TILT community events, such as life drawing classes, remain important parts of our culture. We have established internal Action Teams—including those focused on compassion and curiosity—which allow staff to explore a host of related initiatives.

We are also expanding the types of engagement and inclusivity projects we do, and will continue to advocate for climate and community-focused policy change locally and nationally.

The journey

Pursuing an integrated decentred approach to sustainability will no doubt create discomfort and ambiguity. Acknowledging and dismantling the ways humans have constructed race and racism, their histories, and their enduring realities for billions of people can be daunting.

We’re prepared for this. To be changemakers, we know we must adapt, and ultimately, embrace change. We are past the point where we can attempt to design sustainably without bringing race, class, and equity into our everyday work.

This is the journey of our time. There is no soft, euphemized way to put it.

It is hard work, with no tidy conclusion or foreseeable endpoint. But progress is achievable, and we can all contribute. Our challenge is to be persistent as we evolve our goals to be increasingly equitable and just, and to dignify all people and the planet.

We must do this together, sharing ideas, actions, and resources. And we must support—and challenge—each other to be radically accountable along the way.

[1] World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our common future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[2] Bryan Lee Jr. “America’s Cities Were Designed to Oppress.” CityLab, June 3, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-06-03/how-to-design-justice-into-america-s-cities

[3] “Te Kawenata o Rata.” New Zealand Institute of Architects. https://www.nzia.co.nz/about-us/te-kawenata-o-rata

[4] “Decolonizing Design: The Case for Universal Inclusivity.” Azure Magazine, Oct 15, 2020. https://www.azuremagazine.com/article/decolonizing-design-the-case-for-universal-inclusivity/

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] https://www.kateraworth.com/doughnut/

[8] Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K. et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 461, 472–475 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/461472a