Examples of exclusion in the built environment are all around us – yet most of us don’t notice until we’re directly impacted.

I was reminded of this one lunch hour, when I encountered an unfamiliar sign on the entrance to a popular downtown Vancouver food court – a door I’d opened many times, but never studied closely.

People seeking an accessible entrance, the sign read, should use an alternate entrance on the opposite side of the building. My curiosity took over; I had to investigate.

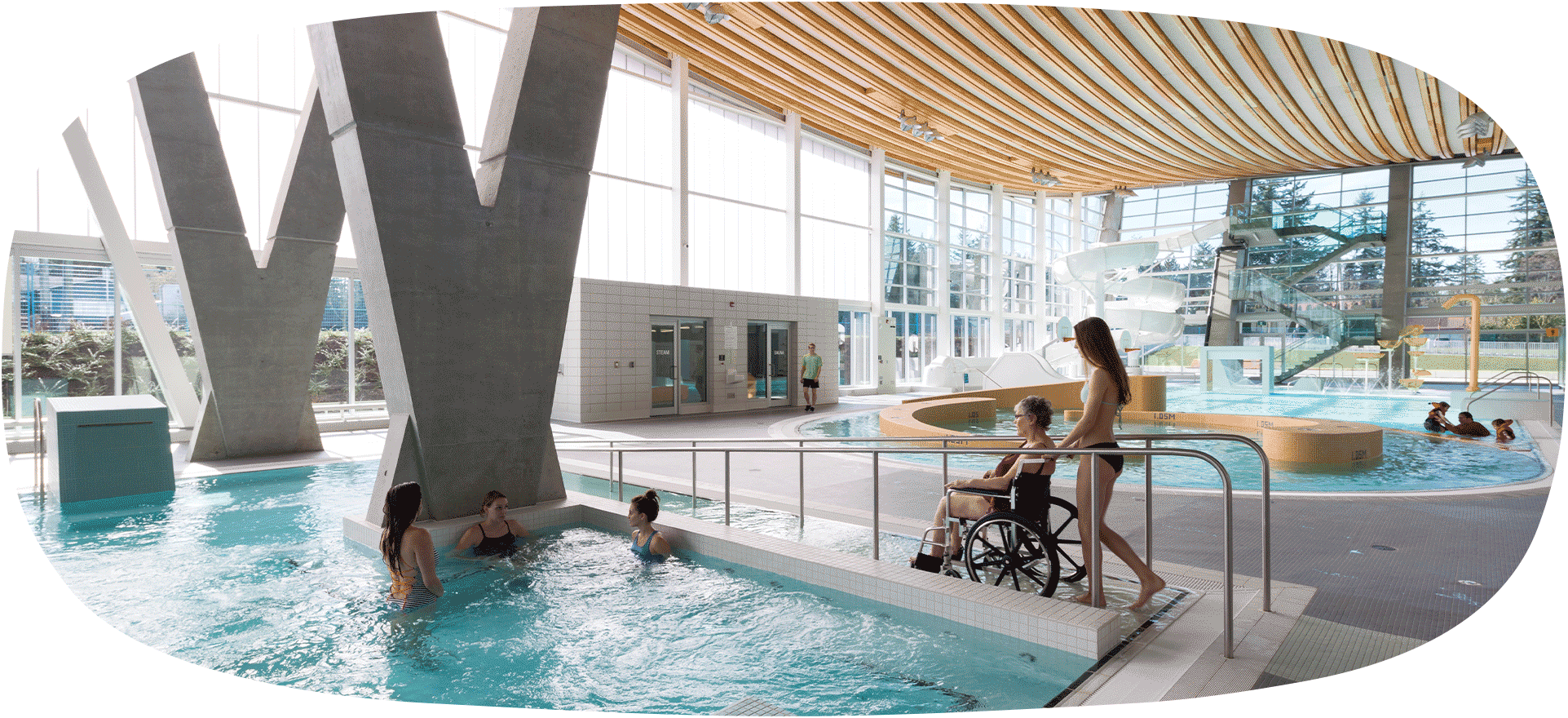

What should have been a simple and dignified alternate route into the building quickly became a time-consuming and ‘othering’ endeavor.

Technically, the building met the requirements of the BC Building Code. Yet its only accessible entrance meant travelling two blocks, admission through a security-guarded lobby, and a gruelingly slow elevator ride through back-of-house auxiliary spaces.

That was just the first hurdle: the next required navigating tight aisles around seats and tables during the midday throng and ordering a meal at too-high counters that lacked the necessary knee clearance for wheelchair users.

And those were just the physical barriers I noticed.

It shouldn’t have been this difficult to buy lunch. Yet scenarios like this are often reality for more than eight million Canadians aged 15 or older (27%), who live with one or more visible or invisible disabilities, according to Statistics Canada’s 2022 Canadian Survey on Disability.

Recognizing the building blocks of exclusion

Many of our schools, workplaces, residences, parks, beaches, and trails needlessly prohibit the disabled. Even more disheartening are the architects, building owners, and operators who deliberately exclude, or remain willfully blind to, diverse needs in the interests of design simplicity or cost savings.

User experience (UX) designer and author, Kat Holmes, perhaps says it best: “Every choice we make as designers determines who can use an environment or product. The mismatches that we create in the process are the building blocks of exclusion.”

I will never forget an email I received after a talk I gave at a national conference for accessibility and inclusion. The sender was an accessibility advocate, living with multiple disabilities, who thanked me for my pointed message.

She said she spent the better part of her days debunking myths among architects and design teams who were satisfied to meet building code minimums and leave it at that. Often, she wrote, her requests were met with “hostile compliance”, rather than a readiness to meaningfully include as many people as possible.

The conversation was sobering: why are we putting the onus on people with disabilities to problem solve their way through – or avoid – the spaces others can freely enjoy?

Changing mindsets

We know attitude, not cost, is the main obstacle to progress.

As a profession, I am imploring us to do better.

Through a collaborative cost comparison study in 2020, hcma and the Rick Hansen Foundation (RHF) debunked the long-held myth that constructing a new building to a Certified Gold level of accessibility (RHFAC* version 2.0) was too expensive.

The data revealed Gold-level certification could be achieved with less than an estimated 1% additional construction cost.

Building solely to the requirements of Canada’s National Building Code, the study found, meant new construction would score an average RHFAC rating of 35%, as compared with the 80% needed to achieve an RHFAC Certified Gold level of accessibility.

The results demonstrate the pitfalls of using code compliance as our only benchmark – and that cost is not the main obstacle. It was a huge win for accessibility.

Since then, we’ve seen many of our colleagues, as well as city councils in Vancouver and Surrey, respond positively to the study findings – going as far as to mandate RHFAC Gold Certification as the minimum accessibility standard for all newly constructed public buildings in those two cities.

It is promising to witness our collective understanding of meaningful access, disability, and neurodiversity shift and broaden. After all, the built environment has the potential to advance both a fuller definition of diversity, and our responsibility towards it.

Even more encouraging? Witnessing a growing desire from our clients to work with people with lived experience – and pay them equitably for their valuable time and input. We believe this is an essential part of understanding what design decisions make the most difference, and how we can do better for future generations.

Tackling wicked problems sustainably

But in our haste to solve accessibility and inclusion issues, we cannot lose sight of humanity’s most pressing threat: the climate crisis.

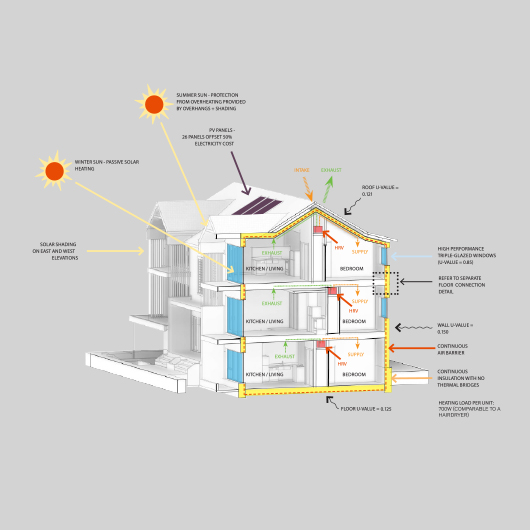

Adaptive re-use – retrofitting and renovating existing buildings to meet the needs of future generations, as opposed to tearing down and building new – is one such way we can lessen our environmental footprint.

And lessen we must.

In 2021, the building industry was responsible for more than a third of worldwide energy demand (34%), and energy and process-related carbon emissions (37%), according to the most recent Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction tabled at COP27 talks in Egypt.

Sobering statistics – particularly when paired with projections from the World Green Building Council that the global building stock is expected to double by 2050 as the planet’s population reaches 10 billion. Along with estimates from the United Nation Environmental Programme (UNEP) that our collective drain on raw resources will double by 2060.

As the Canadian population ages and becomes more diverse, we know demand for accessible and inclusive spaces will surge.

So, it got us thinking: if the need to reuse and reimagine existing infrastructure is so pressing, is it really ‘too difficult and expensive’ to upgrade older buildings to provide similar levels of dignified access as new builds, as we’d commonly been told?

50 years of exclusion

In 2023, we sought more answers about the true cost of retrofitting existing buildings to an RHFAC Gold–certified standard, starting with research into two building typologies where many of us spend most of our days: school and work.

Think back to time spent in Canadian schools built in the last 50 years. Even where entrances were accessible, many key features of learning were not: science, technology, and foods rooms lacked accessible workstations, sinks, and benches; auditoriums had no accessible seating or way of getting on stage. And the education system itself was sometimes built on segregation, with disabled students sent to separate schools or tucked away in basement classrooms.

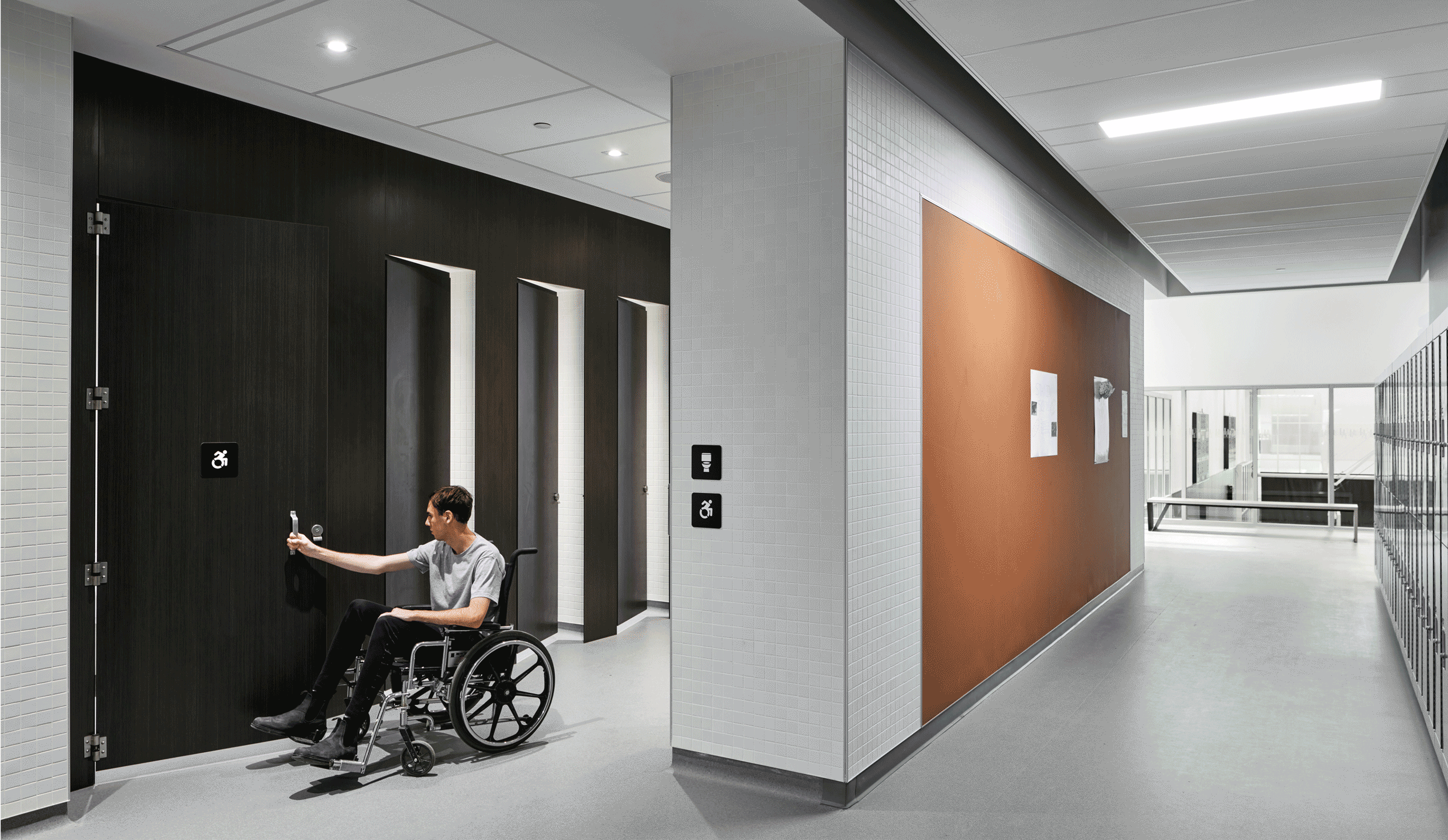

Offices too, haven’t always been particularly welcoming for people with disabilities. In large office blocks built in the last 50 years, it’s common to find some entrances are accessible, others not – and not a single universal washroom in the entire building. Signage is sometimes present but often it’s minimalist or confusing; material finishes are sleek and sophisticated but lack the colour contrast and tactile elements that help so many people find their way.

These buildings met code requirements when they were designed. But rather than removing barriers, they’ve put an incredible burden on people with mobility, hearing, vision, and other challenges to navigate these spaces in a safe and dignified way.

Making the most of what we’ve got

Our goal through this second cost comparison study was to investigate the feasibility of retrofitting existing buildings to achieve RHFAC Gold (an 80% rating) by determining the cost and strategies for accessibility upgrades.

We discovered that an RHFAC Gold-level of certification (version 3.0) could be achieved through upgrades at less than an estimated 0.5% of the replacement cost of an office tower (base buildings only), and for less than 1.5% of the replacement cost of a K-12 school.

In terms of cost per square foot of gross floor area, this translates to upgrade costs of $1.50 for office buildings and $9.00 for school buildings – figures that dropped to mere cents when renovations were completed or amortized over five, 10, or 15 years.

One of the key takeaways? Retrofitting existing office buildings and schools to achieve a Gold-level of accessibility is feasible if building owners and operators integrate these improvements into routine maintenance, planned projects, and potential funding opportunities such as accessibility grants.

And it can be surprising just how many accessibility upgrades can be implemented at little to no cost: things like moving furniture and waste bins to improve clear widths and turning aisles; adding braille lettering to directory boards and room signage; or moving washroom accessories and dispensers to accessible heights and locations.

It’s a reminder that the path to true meaningful access and inclusivity is paved by a willingness to act and think differently; by listening to people with lived experience; and through a commitment to doing the right thing.

We must rethink our approach to meaningful access: from ‘hostile compliance’ to compassion.