National AccessAbility Week is upon us – with it, comes an opportunity to reflect on our responsibility to design communities that are inclusive and accessible for everyone.

One of my first projects as a young architect was the award-winning Walnut Grove Aquatic Centre in Langley, B.C. I remember the pride I felt when it opened in 1999; the palpable joy my daughter radiated during her first dip in the pool.

Shortly after, I received a letter from a fellow parent. She congratulated me on the successful completion of the pool but lamented that her own daughter could not use the facility due to the specific nature of her disability.

Through more carefully-considered design, this would not have been the case. It was a crushing epiphany – that, despite following all the Building Codes, I hadn’t done nearly enough to ensure meaningful accessibility.

It’s something I’ve worked hard to change ever since.

Note:

This work was originally published during National AccessAbility Week on May 31, 2022, by Canadian Architect: "Canadians want architects to help create more inclusive and accessible communities”.

Rethinking accessible and inclusive design

As our emotional and physical needs evolve through various stages of life, so do the associated barriers. These are often intersectional – encompassing social, cultural, economic, political or colonial barriers, as well as physical ones.

Nearly half of Canadian adults have a permanent or temporary physical disability – or live with someone who does, according to statistics from the Angus Reid Institute. This number is compounded by those with invisible disabilities.

Meeting minimal standards of the Building Code can no longer be considered a marker of success. Truly public buildings must accommodate all, regardless of ability, age, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, or belief.

Canadians think so too.

A growing public call for change

Recent research conducted by the Angus Reid Institute, in partnership with Rise for Architecture, found Canadians were near-unanimous in prioritizing accessibility (96 percent), aesthetic beauty (92 percent) and sustainability (90 percent) in new buildings.

These results echo what I’ve long believed – that our surroundings shape our future, and that the design of our communities has a significant impact on our potential, both as individuals and a nation.

Research shows well-designed buildings are vital in supporting our goals of sustainable, socially equitable, and inspiring communities. Yet, here in Canada, we haven’t always considered this.

More than half of Canadians (51 percent) say development in their community is “poorly planned,” Angus Reid’s poll reveals.

Forget business as usual

With billions of dollars in public infrastructure spending being contemplated to help Canada emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic, we can’t continue with status-quo design thinking.

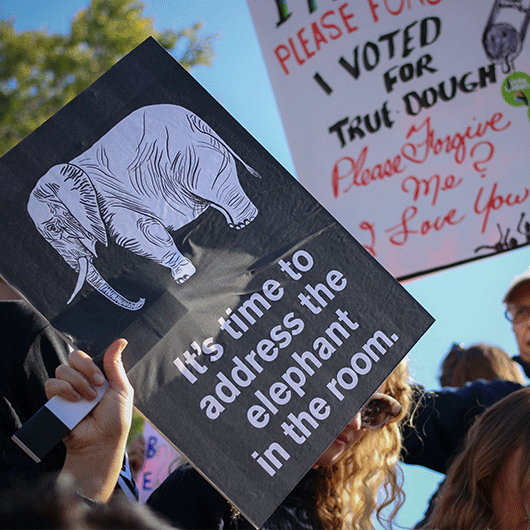

Canadians are asking architects and consultants to incorporate wide-ranging universal design features and philosophy into the built environment.

The projects we build today will be around for the next 50 to 75 years; we must avoid creating new barriers and demonstrate the value of removing existing ones.

And while progress can seem sluggish, I am encouraged by a few recent developments in legislation, tools and training.

The Accessible Canada Act, for example, has mandated that all new federally-regulated infrastructure must meet measurable and meaningfully-accessible best practices, helping people of all abilities contribute and participate in their communities.

Provinces, too, are implementing their own accessibility-focused legislation.

While not without areas for improvement, these are important steps forward. More action is needed.

Rick Hansen Foundation Accessibility Certification

One tool I have been using to improve physical accessibility in projects is the Rick Hansen Foundation Accessibility Certification™ (RHFAC) program.

It recognizes and rewards innovative approaches to universal design with two levels of certification – RHFAC Accessibility Certified and RHFAC Certified Gold – which are awarded during design or after occupancy.

RHFAC encourages professionals to go beyond minimum code compliance, exploring creative ways to broaden the appeal and accessibility of our buildings for people with varying disabilities affecting mobility, hearing and vision.

I find it heartening that the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC) recently announced a collaboration with the Rick Hansen Foundation and PowerED™ by Athabasca University, to expand the capacity of accessibility certification training for the architectural community.

Initiatives like this incentivize RHFAC training through discounts and professional education credits – and more importantly – empower architects with the tools to meaningfully understand accessibility and inclusion from a cross-disability lens.

An eye to the future

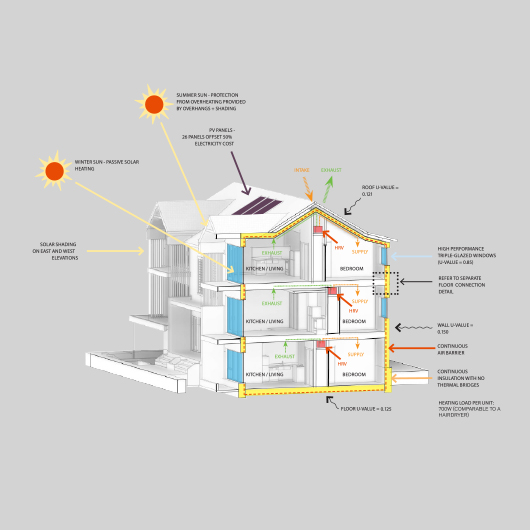

Our profession embraced the environmental sustainability movement at the beginning of the millennium; we must now widen our focus to embrace the inclusive design movement.

Certification tools – while never completely comprehensive – can play a key role in encouraging the building industry to change, much in the same way we saw green building tools transform our response to the climate crisis.

Collectively, we must invest in developing our knowledge and expertise to address an even wider range of complex, intersecting barriers.

After all, we have a duty to build a better future for all Canadians; to ensure our communities are more inclusive and accessible for everyone.